The Case for Friction: When Ease Becomes the Enemy

I spend my days removing friction from digital products and experiences, but I've been asking myself a heavy question: what do we lose when everything becomes too easy? This post explores the tension between building frictionless experiences and preserving the resistance that keeps us human.

Published on: January 20, 2026

I spend my days removing friction. As a design manager at IBM, that's literally the job: find where people struggle, smoothen it out, make the path effortless. Every prototype review, every usability test, every design decision is oriented toward one goal: reduce cognitive load, eliminate confusion, get people from A to B as efficiently as possible.

But lately, I've been thinking about what we lose when everything becomes TOO easy.

The Cut recently published a piece about "friction-maxxing," the practice of building up tolerance for inconvenience in a world that sells us frictionless living at every turn, and I encountered it just as I was in the middle of reading "The Comfort Crisis" by Michael Easter. The timing felt right. We've spent years letting algorithms dictate our behavior, from what we read to how we plan our grocery runs. We've outsourced minor annoyances to tech and AI so efficiently that basic thinking mechanisms now register as friction.

And here's where it gets a lil uncomfortable for me: I'm part of that machine.

The Paradox I Live In

There's a strange tension in advocating for friction when my entire career is built on removing it. But here's what I've come to understand: context is everything. The friction we remove in healthcare products isn't about making life more convenient, but about making care accessible. When a nurse can document a patient interaction in seconds instead of minutes, that's not laziness; that's life-saving. When a patient can understand their treatment plan without translating medical jargon, that's dignity.

I witnessed this last month when my stepmom Greta had a stroke and spent three weeks in an ICU in El Paso. None of us had cared for a stroke patient before, and my father-in-law was suddenly navigating complex medical conversations while trying to process what was happening to his wife. My wife Lexi had recently purchased Plaud, an AI voice recorder and note taker, for her own work and realized it could help her dad capture the critical information doctors shared during their brief visits. With Plaud pinned to his shirt, he could focus entirely on understanding what the doctors were saying rather than frantically scribbling notes. The AI handled the documentation, giving him the mental space to ask questions, absorb difficult news, and share accurate updates with our family. In that scenario, removing friction through AI didn't diminish the human experience; it protected it.

But the same tools that help us build those experiences are increasingly being positioned as solutions to all of life's minor inconveniences, and that's where I think we've gone wrong.

In "The Comfort Crisis," Michael Easter writes about how our brains evolved to solve problems, to struggle, to work for rewards. When we eliminate all resistance, we don't just lose the satisfaction of overcoming challenges; we lose the development that comes from the struggle itself. Recent research backs this up: an MIT study found that frequent use of large language models can interfere with learning. Thus, the mental resistance training we get from friction isn't optional; it's how we stay sharp.

Just Because We Can, Should We?

This is the truly THE question that has been consuming my days. Just because we can build it using AI, should we?

I work with AI-augmented design methodologies that can accelerate product development timelines dramatically. I've designed complete healthcare products in three months using these tools. The efficiency is real and the capability is astonishing, but I'm trying to be increasingly careful about where I deploy it. There's a difference between using AI to handle truly tedious work (renaming layers, synthesizing research, generating copy variations for testing) and using it to bypass thinking altogether. The former gives us time back whereas the latter hinders our ability to think critically, to make intuitive leaps, to develop our own taste and judgment.

I've started asking myself a new question in my work: "Does removing this friction make the experience more human, or less?"

Responsible Friction

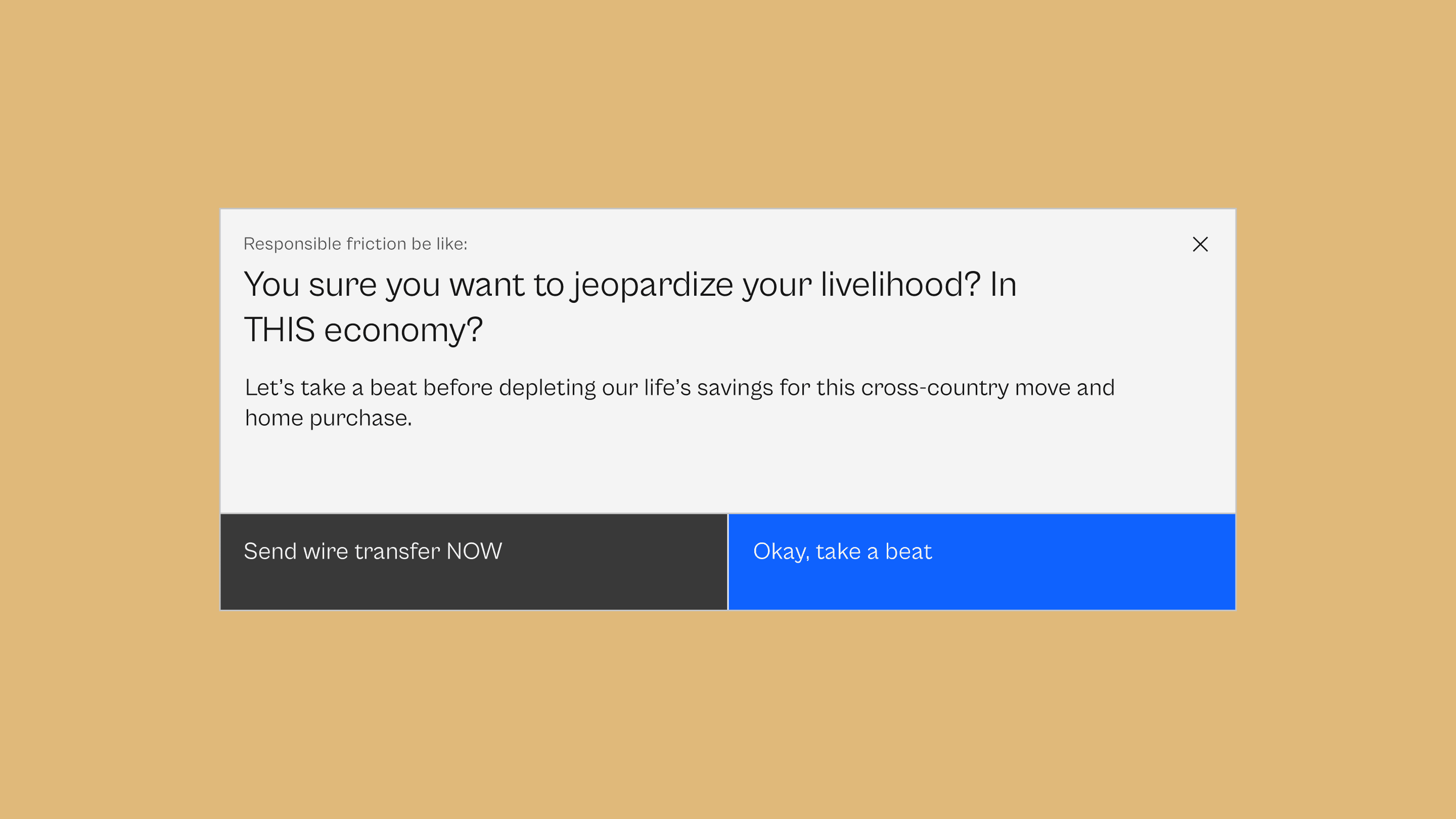

This tension has led me to a new framework I've been exploring: responsible friction. This is friction we intentionally design into experiences, not because we're being lazy or inefficient, but because the pause serves a critical purpose.

For example: when someone wants to delete a healthcare record, that modal that appears asking "Are you sure?" isn't annoying interface design, but rather a safeguard. That moment of friction gives you time to consider the irreversibility of the action, to catch an accidental click, to protect data that matters. Similarly, two-factor authentication when logging into your bank account to transfer money or make a payment adds seconds to your experience, but those seconds are protecting you from catastrophic monetary loss.

I experienced this firsthand recently when I wired nearly all of our life's savings to a title company for our home purchase. USAA made me complete four additional verification steps before allowing the transfer. Each one felt like a small eternity when I was anxious to complete the transaction for us to meet our desired closing date, but what surprised me was that those steps didn't increase my anxiety. They had actually reduced it. Each verification was a moment to pause; to confirm I hadn't made a mistake; to know that if someone else had gained access to my account, they'd face the same gauntlet. The friction that USAA had built into the wire transfer experience wasn't frustrating, but instead reassuring.

Responsible friction is about recognizing that not all speed is good speed (And this is coming from someone who only ever loves moving fast!) Sometimes the best design is the one that makes you stop and think. These aren't frustrating obstacles, they're thoughtful interventions at moments where ease could lead to harm.

In my work, I'm constantly evaluating: Is this friction protecting the user, or just slowing them down? Is this pause creating space for better decision-making, or is it just bad UX? That difference matters.

Where Friction Belongs

So where do we need to keep friction? Here's what I'm experimenting with in my own life:

Stop outsourcing thinking. I definitely still use AI for research and ideation, but I've been mortified at the use cases I've observed from my loved ones in which they use AI to draft birthday texts…heartfelt pleas….messages that really should come from ourselves and not from an LLM. The journey of finding the right words myself is where my voice lives.

Embrace productive boredom. I love waiting in line without scrolling on my phone. Sitting with a problem before Googling the answer. Letting my mind wander during my commute instead of filling every moment with an audiobook or a song.

Choose the harder path sometimes. This year, I want to practice cooking from a cookbook instead of asking AI for lunch and dinner ideas. Going to the grocery store with no ingredient list and relying on my experience in the kitchen to cook up something new. Making phone calls instead of texting.

These aren't rejections of technology. They're conscious choices about where convenience serves us and where it diminishes us.

The Professional Implications

For those of us building digital products, this matters beyond our personal lives. If we're not careful about where we remove friction, we risk building experiences that are efficient but empty, fast but forgettable, smooth but soulless. The goal isn't to make everything hard for the sake of difficulty. It's to be intentional about what we optimize for. Sometimes the best design is the one that slows you down, makes you pause, asks you to think. Not every interaction needs to be instantaneous. Not every task needs to be automated.

This is where responsible friction becomes a design principle, not just a safety feature. We need to distinguish between friction that protects and friction that frustrates. Between pauses that serve the user and obstacles that serve no one.

In healthcare, we remove friction so people can focus on what matters: healing, caring, living. But we should be suspicious when that same logic gets applied to everything else because life isn't a workflow to be optimized; it's meant to be felt, struggled with, learned from.

Building Tolerance

Friction-maxxing isn't about making life harder. It's about building tolerance for the natural unpredictability of being alive. It's choosing to preserve the small resistances that make us human: the effort of thinking, the discomfort of waiting, the work of connecting. As someone who removes friction professionally, I'm learning to be more discerning about where I remove it personally. Not all ease is progress. Not all efficiency is improvement.

Sometimes the friction is the point.

The question isn't whether we can eliminate inconvenience. The last year has clearly demonstrated to us that we can! The question is whether we should. And increasingly, my answer is: not always.

As AI continues to permeate every single industry and every part of our day-to-day, I implore you to ask yourself: what friction are you choosing to keep in your life? Not because you can, but because you should?